Like many law enforcement agencies, Washington State Patrol (WSP) has employed laser scanning as a tool for scene measurement and documentation. Today, twenty-one year WSP veteran Rod Green is taking the use of forensic scanning to new levels using Trimble solutions.

Green has been conducting accident and crime scene reconstructions for 14 years. In addition to collecting and analyzing information, he is working to improve the reconstruction process on-scene and in the office. The results have drawn attention in Washington and surrounding states.

What makes Green’s work unique is his use of experience and knowledge to simplify and expedite the process of collecting and analyzing information and evidence at accidents and crime sites. Green combines high-tech hardware and software tools with logic to make major improvements in reconstructing the scene.

Green has worked in every area of reconstruction, from data collection to the production of drawings. But, the technology doesn’t change the core mission of public safety and law enforcement. “I’m not so concerned with how pretty the point cloud looks as I am with getting the details—all of the details—to accurately gather measurements of the scene for reconstruction,” Green said.

Green believes that laser scanners’ ability to gather huge amounts of information can play an important part in producing reports, drawings and exhibits that contribute to the successful resolution or prosecution of a case. But for scanners to become common tools, they must easily blend into the work of people who are already very busy.

Speed and Accuracy

Investigators onsite of fatal collisions and crime scenes face several challenges. They need to collect comprehensive information in an accurate, systematic manner. Often working at night or in inclement weather, they must capture data quickly while the scene is fresh and before rain or snow can destroy evidence.

Quick work is also critical to reducing the length of road or lane closures, which are costly and inconvenient to the public. According to a 2015 report by the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA), costs attributed to congestion caused by fatal crashes in 2010 including travel delay, excess fuel consumption, greenhouse gases and pollutants totaled $189 million. On average, a fatal collision resulted in a closure of nearly 3.75 hours. By using laser scanners for data collection, Green and his WSP colleagues showed that they could reduce the time on site while increasing the quality and quantity of information they gather.

Investigators must also guard their own safety. Often, they are working near traffic or other hazards. Different measurement methods such as total stations and baseline-and-offset techniques may require several people to capture and record the data which could mean closing more lanes. Total station measurement often requires a second person at the site to hold the prism rod; that person could be working on some other aspect of the investigation.

Green knows of jurisdictions that have closed busy roads for 6 hours or more to complete measurements with a total station. A laser scanner, however, operates autonomously, to reduce the time and number of people needed for measurement and documentation while also minimizing exposure to dangerous traffic.

In addition to on-scene measurements, reconstructors must manage and process the data to produce the information needed by investigators and district attorneys. They need to focus on the pertinent details while maintaining data integrity and the chain of evidence. Their finished products are exhibits, reports and analyses that provide the basis for the accurate depiction of the scene and events. Green has developed a combination of hardware, field procedures, software and data management that reduces time on site and produces finer detail throughout an investigation.

Forensic Scanning to Gather Evidence

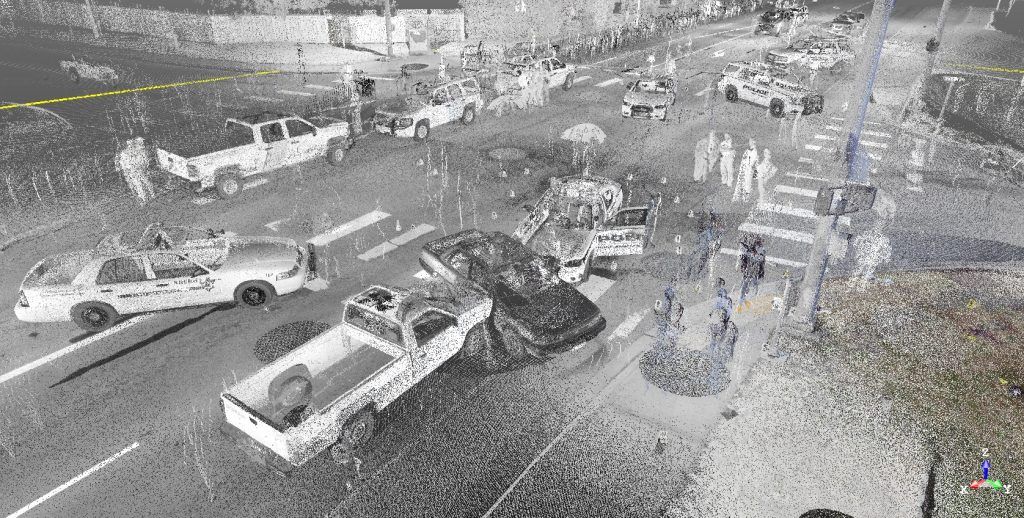

Scanners have been used in scene reconstruction for nearly 20 years. A scanner uses laser technology to collect a large number of closely-spaced measurements and produce a “point cloud” of 3D points. By setting the scanner in several locations around a scene, investigators can capture multiple point clouds to develop a 3D snapshot of the location. Even small or subtle features such as shell casings or tire marks can be captured using the scanner and point cloud.

Scanners have been used in scene reconstruction for nearly 20 years. A scanner uses laser technology to collect a large number of closely-spaced measurements and produce a “point cloud” of 3D points. By setting the scanner in several locations around a scene, investigators can capture multiple point clouds to develop a 3D snapshot of the location. Even small or subtle features such as shell casings or tire marks can be captured using the scanner and point cloud.

The scan data is then transferred to computers for archival and processing. The multiple scans are combined into a single point cloud, which provides a complete view of the scene.

However, large point clouds come with challenges. “There are people who look at a point cloud and say they can’t see the details,” Green said. “That is usually because it wasn’t scanned or processed correctly. We want to avoid the trap of not seeing the evidence for the cloud. We do not want just a huge cloud; we want better management of the cloud.” The solution comes from integrating the processes from collection through to final reports.

That integration begins in the field, where WSP uses a Trimble TX5 scanner. The scanner simplifies the work for scene investigators by providing preset scanning modes that capture data at different levels of resolution.

Similar to preset modes on a digital camera, users can select the scanning mode to fit the detail needed at each setup on the site. Green has developed guidelines for WSP investigators that recommend the appropriate mode for capturing different types of details and evidence. “We like the presets,” he said, “because we can teach our people what mode to use in a given situation without having to calculate resolution.” Scanning at higher resolution requires a bit more time but can capture small details. “I might need to capture shell casings or faint tire marks; for that we might scan at high-resolutions,” Green explained.

Data from the scanner goes to the office, where detectives use Trimble RealWorks software to combine the scans and begin analyzing the scenes. The software can use “plane-based” and “cloud to cloud“ registration to merge multiple scans—the technique helps reduce the need for on-scene investigators to handle the spherical targets commonly used in many scanning projects. Although target spheres are needed in some situations, Green said the plane-based and cloud to cloud approach is much simpler and faster for field investigators—so much so, it’s become the default method.

Eliminating the targets is just one way the software component of the integrated system helps make the job of on-site personnel and office faster and easier. For example, even when working at low resolution the scanner may collect thousands of points on a road— far more than needed to correctly depict the surface. The software can reduce the density of the points to preserve the accuracy of the information while eliminating clutter that could potentially distract or confuse a jury.

The main benefit of RealWorks, Green says, is to clean unneeded points. Troopers need to work within the scene and traffic during scanning, so they are sometimes measured by the scanner resulting in superfluous or “parasite” points. The software’s Auto Classification feature can place designated objects (ground, poles, vegetation, buildings) into designated layers and also remove the parasite measurements from the finished point cloud. The feature allows for quick processing to finalize the cloud by removing all unneeded measured points.

As soon as the main point cloud is in place, the office starts creating reports and diagrams. Using EdgeFX reconstruction software, Green can draft maps and models in 3D. Points that are superfluous or irrelevant to the case can be moved to separate layers that are switched off, but are still preserved to meet the essential chain of evidence requirement while maintaining integrity of the scene’s data. When the point clouds are completed, the clouds and analyses can be supplied to prosecution teams. RealWorks includes easy viewing software that enables attorneys to view and “walk through” a point cloud to gain a detailed understanding of a scene.

Investigators can add evidence markers, vehicle models, trajectories and more—the software can even simulate how cars are crushed in a collision. The information can be used to produce diagrams and animations for courtroom presentations or can be sent for specialized analysis. The result is a concise representation of the scene and events—all backed by detailed, defensible data.

Performance & Results

The speed of the scanning system is evident in the results. Green described a recent murder investigation in which a local jurisdiction had mapped the crime scene — a series of trails leading from a trailer park to a swamp. Using a total station, it took three people to do the work. The team needed roughly six hours and required five setups of the total station. They captured a total of 600-700 points just to produce the drawing. To demonstrate the power of scanning, they repeated the mapping using the TX5 scanner. The work in the field required only 75 minutes and captured the same trails. With millions of points instead of a simple drawing, the team produced a full 3D point cloud ready for drafting that contained far greater detail than the total station work.

Officers investigated a vehicle collision at a second location that also included a shooting. Although capturing the complicated scene required 31 separate scan setups, Green estimated the scanning was completed in less than two hours. When the scan data arrived in the office, he needed only six hours to perform the registration, cleanup and drafting. Depending on the review process, Green said that the entire timeline to produce a full report could be less than two days.

One of scanning’s most valuable features is the ability to preserve a scene while it is fresh so officers can “virtually” revisit it after the fact. For example, an object not deemed pertinent early in an investigation may turn out to be important. By using the point cloud, investigators can return to the virtual scene at any time. They can use the virtual return visits to extract or confirm details on the object and its location long after the on-scene events and investigation.

What’s key to Green’s success is his understanding of what goes on at the scene and beyond. By using a holistic approach to reconstruction data collection and analysis, he is helping to simplify the work of officers in the field as well as in the office. The result is faster, safer work, with better results.

About Trimble

Trimble core technologies in positioning, modeling, connectivity and data analytics enable customers to improve productivity, quality, safety and sustainability. Learn more at Trimble.com.